When my career first started, there was nothing more exhilirating than being asked about it. “I’m a writer,” I’d announce. “A ghostwriter.”

I was jetting off alone, laptop in tow. Just like my dad had promised, I hadn’t gone to college and I was doing better than good. I was working for myself, the ultimate mark of success.

But, even at twenty, it wasn’t really so glamorous. I remember taking in the ocean view on my first international trip, trying not to calculate the money I was burning through every hour while I attempted to delay a big project that had been assigned to me that morning. I never understood how writing anything could be so urgent, and I still find great irony in the limits of freedom that come with freelancing.

The work-life imbalance I tolerated fine. Working seven days a week is not that hard when you can do it in your comfy clothes at any hour of the day. Really, it was the tech bros who did me in. Shortly into my career, those with any editorial sense were shooed away from leadership roles and replaced with a metric man in his 30s who would critique our work using software instead of his own eyes.

My job devolved from creating content to assembling it.

“Writer” hardly seemed like a fair thing to call myself anymore. At the peak of my career, I felt nothing but a shameful disinterest in it. But, I told myself that’s part of life. I didn’t need to love what I was doing. It’s flexible and it’s dependable, right?

Until it wasn’t. My fiancé and I had discussed AI and the havoc it would wreak over the course of many dinners. Admittedly, I was in denial about just how soon it’d happen, but on its own I could’ve handled it fine. It’s just that life has a way of bringing everything to a head at once.

All in a week, my parents boarded a plane and left the country. My best friend who’d been at my side for the better part of my life passed away. My fiancé learned his heart was failing, and the doctors couldn’t tell us why. And, almost comically, just as I reassured myself that I’d convince him to take off work for awhile while we figured it out, my career came to a screeching halt.

The mega agency who had long made up the brunt of my income, the one who had been publically warning companies against using AI-generated content for a year, revealed they had been training an AI model on the work of myself and my colleagues all along, and they didn’t need us any longer. Thanks.

In hindsight, I can admit I had somewhat pitifully resigned myself to the notion that I must quit writing right then, because that’s what the universe seemed to expect of me. It felt as though everything I loved was being taken away, so it was only fitting my career would be taken with it. It was almost an act of defiance; an unsatisfying attempt to feel in control. I could’ve betrayed my morals and began training content bots, which was offered to many of us like a consolation prize, but I wasn’t willing to end my career that way. So I set it down. Not gently. I guess I threw it on the ground.

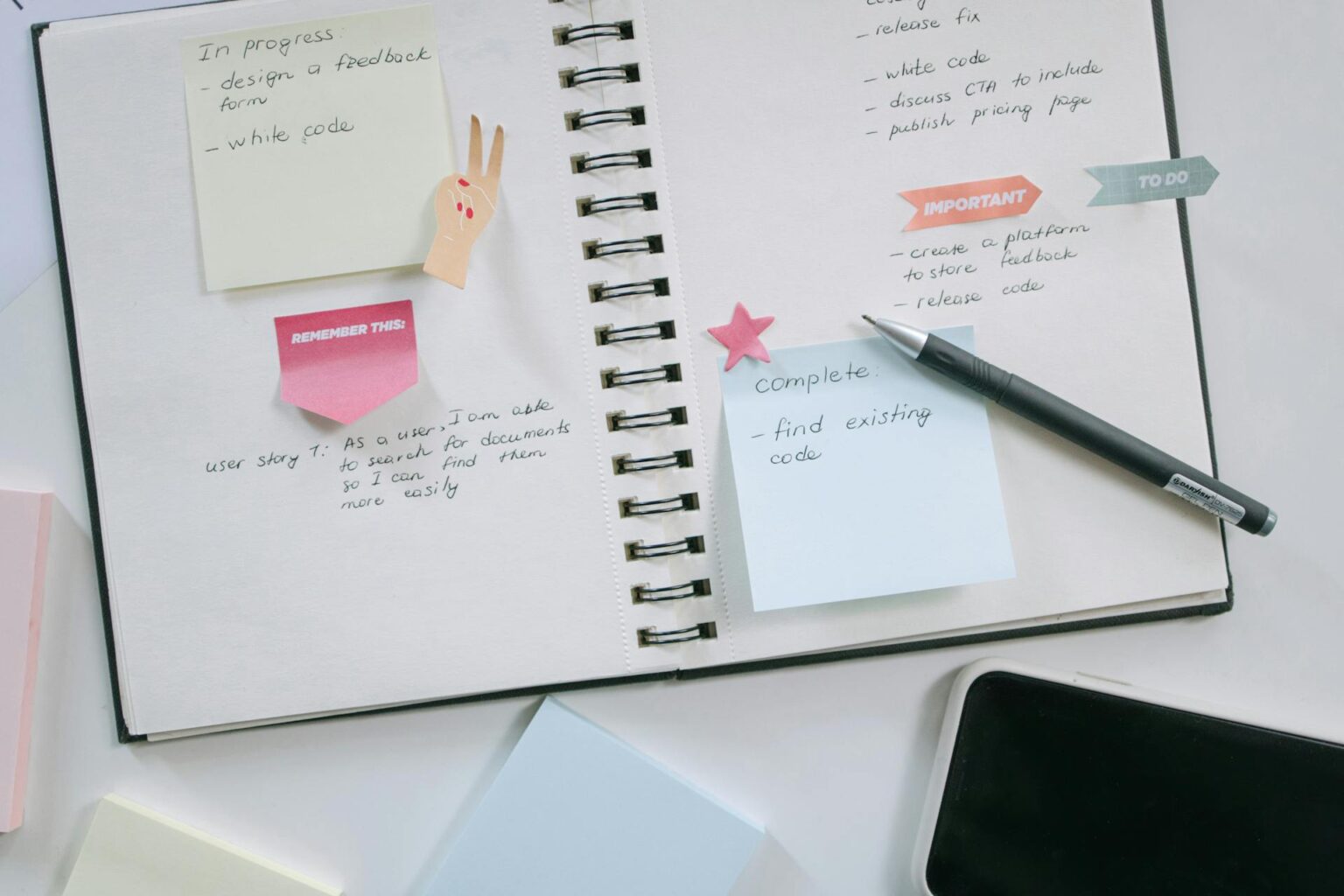

For the rest of 2023, I wrote precisely two things:

- A string of words for Krissi’s headstone.

- A letter to Mayo Clinic.

2024 was spent going back-and-forth to Arizona and fighting over the necessity of every new test with the insurance company as we hoped for answers.

2025 started out helplessly sitting alone in Mayo’s third-floor waiting room, trying not to picture my fiancé’s open-heart surgery as it unfolded. Two hours later than expected, the surgeon finally called me and I hung on his every word. “He’ll be waking up in the ICU soon. In a year, it’ll be like there was never anything wrong at all.”

As it turns out, life doesn’t always do its worst to you.

We spent many weeks in Phoenix after that, just in case. We talked a lot. I thought a lot. Finally feeling safe enough to dream about the future again, I traced back my steps. I pondered how writing as a career had come upon me. An obvious skill fused with a well-timed offer to edit a book straight out of high school.

Never had I looked in the mirror and declared, “I want to be a writer.”

I recalled sitting at the family computer when I was six years old, typing up short stories in a much too large font and begging my older sister to print them out so I could bind them with staples and tape. I remembered all the lunch hours spent in the library at school. All the journals I filled as a teenager.

Then it dawned on me. Long before thoughts of a career ever crossed my mind, I was already writing. I have always been writing.

Writers start writing before we realize what we’re doing. It’s instinctual. Irrestisible.

As this long year comes to a close, I’m finishing it with a far brighter outlook than I started with. I’ve wiped clean the website I set up a decade ago and in its place I’ve put this. An invitation to self; a place without concern for metrics. A chance to go back to the place I started: Writing simply for the sake of writing.